Archive - Physicist of the Month 2025

January 2025

Ingrid Krumphals, Professor for Physics Didactics at the PH Steiermark

About myself and my work

Ever since early childhood, I have always been interested in the question - why? Because of my curiosity and my frequent questions, those around me were often confronted with this and often had to explain it. This goal of understanding nature and then being able to explain it to others ultimately led me to study physics teaching. After a few years of teaching and studying for a doctorate, I took the path into science and am now a professor of physics didactics.

So I am specifically concerned with how physics can best be learned and taught, in particular how physics content can be conveyed in an understandable, exciting and effective way. Through my research, I want to contribute to the positive development of the educational landscape so that young people are better prepared for the challenges of the future.

For me, the focus is particularly on promoting future literacy - the ability to actively prepare for future developments - and scientific literacy - the ability to think scientifically and make well-founded decisions. These two skills are essential to act safely and independently in a rapidly changing world. I am convinced that education is the key to enabling a sustainable, fair and good or better future for all.

What can be done to achieve more equal opportunities in physics?

In my opinion, equal opportunities will be achieved when we stop thinking in terms of differences and finally live equality as a matter of course. Instead of concentrating on the differences between people in their diversity dimensions (such as gender, origin, ethnicity), we should focus on what connects us as people. An inclusive culture begins where we see diversity as a strength, not a challenge.

A sentence that particularly inspires me comes from Ursula von der Leyen:

"If we include all talents, we can make the impossible possible."

To promote equal opportunities in the field of physics, we need not only role models, i.e. visible role models who show that physics is for everyone. We need the whole of society: e.g. radio or television presenters who speak positively about physics (and STEM subjects) and arouse interest instead of labeling physics as difficult; Parents who encourage their children to follow their natural curiosity about the world and discover physics as something exciting and, above all, helpful; and simply all people who do not see physics as something abstract or difficult, but at least approach it with an open, neutral attitude. This collective support creates an atmosphere in which young people are encouraged to go their own way - regardless of stereotypes or prejudices.

I have experienced for myself how important it is not only to demand equal opportunities, but to actively live them - from an early age. It begins in education, in lessons and in everyday encounters, in which we encourage children and young people to look beyond the "socialized horizon". We should encourage everyone not only to see opportunities, but also to use them and live them. Particularly in my position as a woman in a leadership role, I have learned that true strength lies in supporting others and creating space for new perspectives. Equal opportunities means not only giving everyone access, but also giving them the courage to go their own way. Another important aspect is to consciously consider other dimensions of diversity: origin, gender, social background or individual living conditions. We all have the responsibility to see this diversity as an enrichment.

"Diversity drives innovation - without it, we lose out on the perspectives that can change the world." – Megan Smith

Ingrid Krumphals is a professor of physics education and director of the Center for Didactics Research in Science and Technology Education at the Styrian University of Education. If you would like to learn more about her and her work, here is the link to her website and here is the link to the NATech Center (both websites only available in german).

Februar 2025

Iva Březinová, Assistant Professor for Theoretical Physics at the TU Vienna

About myself and my research

From a scientifically early age on, I was fascinated by quantum mechanics and how quantum effects play a role in everyday things surrounding us, from the properties of materials to modern technology. Even more fascinating to me is the fact that we have the mathematical tools to describe all these effects, namely the Schrödinger equation. The Schrödinger equation can be formulated for virtually arbitrarily complex systems, but we can only solve it for systems with very few particles, even using today's largest supercomputers. Thus, our considerable understanding of the microscopic world is based almost entirely on approximate methods for solving the Schrödinger equation. Historically, the focus has been on systems in equilibrium, but more recently, as the experimental tools have become available, research has turned to systems strongly driven by external fields. In this way, we have a tuning knob that allows us both to explore quantum systems with unprecedented control and to induce new properties that can potentially be exploited in future quantum technological applications. This is the starting point of my research. My group and I focus on finding methods to approximately solve the Schrödinger equation for non-equilibrium and driven systems in cases where correlations between the particles are important. In applying our methods, our interests are very broad, but we always strive to study systems that are experimentally relevant. These systems range from multi-electron atoms to two-dimensional materials.

What can be done to achieve more equal opportunities in physics?

If we want to increase the number of women studying physics, we have to start early, and female physicists as role models seem to be an important tool. Statistics at my university indicates that an overwhelming number of our female students have benefited from a network of family members or friends with a STEM background when deciding what to study. This data suggests that we are losing young women who do not have access to such networks. Schools and outreach activities at universities could help address this imbalance by showing that being a physicist is a great career for women as well. Speaking of careers, I see another area for action. From my personal experience, it is much more difficult for women to combine a career and a family with small children, mainly because early childcare is almost exclusively taken over by women. These career breaks then overlap with critical periods in the scientific career, making it difficult to compete with colleagues without childcare obligations. Therefore, it is crucial to take into account the academic age corrected for childcare and other career breaks when evaluating the performance of scientists. In my opinion, the care of very young children should increasingly be perceived as something that is shared equally by both partners, both in academia and in industry. In this way, career breaks due to childcare would not almost exclusively affect women. Unfortunately, we are far from that. In academia, an additional stumbling block is the fact that a scientific career requires a high degree of mobility and a willingness to spend years on short-term contracts. It would help young scientists in general, but especially women who plan to have families, if it were possible to get a position that would allow them to plan their careers earlier.

Iva Březinová is assistant professor for theoretical physics at the Vienna University of Technology and a member of the Erwin Schrödinger Center for Quantum Science & Technology (ESQ) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. If you would like to learn more about her and her work, here is the link to her research group's website and here is the link to her ÖAW website.

March 2025

Ille C. Gebeshuber, Associate Professor for Experimental Physics at the TU Vienna

About myself and my research

My name is Ille C. Gebeshuber. I am Associate Professor of Experimental Physics at the Institute of Applied Physics at the Vienna University of Technology. My academic career began with a degree in Technical Physics at the Vienna University of Technology, followed by a doctorate in Technical Sciences. In my diploma and doctoral theses, I focussed intensively on hearing theory and investigated how our ear perceives tiny signals.

I am currently working on bionics, an interdisciplinary field of research that draws inspiration from biological structures, materials and processes to develop sustainable technical innovations. I am particularly interested in researching bio-based and biodegradable materials that can be used to create functional structures. Inspired by nature, which uses local resources and water-based chemistry to achieve efficient and sustainable solutions, I endeavour to apply insights from bionics. My work is characterised by an interdisciplinary perspective; my students come from the fields of physics, materials science, chemistry, architecture, economics and art. I also collaborate with the University of Applied Arts to teach art-based research to student teachers in the Department of Technology and Design.

What can be done to achieve more equal opportunities in physics?

In order to achieve equal opportunities in physics, it is of great importance to present children with inspiring role models at an early age who can introduce them to the fascination and exciting possibilities of physics. Physics enables us to be curious throughout our lives, to ask questions and to actively contribute to improving our future. If girls and boys are treated and encouraged equally from the outset, there will be no rigid role categorisation into ‘male’ or ‘female’ professions. Increased diversity in physics opens up a wide range of perspectives and enriches the spectrum of issues that need to be investigated.

I am actively committed to equal opportunities and am active as a representative on the Working Group for Equal Opportunities and in various outreach programmes at TU Wien. These include the Daughters' Day, the “Women in Technology” initiative and other programmes aimed at getting young people interested in physics, regardless of their gender or background.

My earliest experiences of unequal treatment came later. As a child, I was able to pursue my interest in science unhindered. During my studies, however, a professor asked me during an exam: ‘Why are you studying physics and not at home at the cooker?’ I answered simply: ‘I love physics. For me, it's the most exciting and fundamental subject area.’ That settled the debate.

In the course of my career, I have experienced both disadvantages and targeted support. Overall, I feel the balance is balanced. Times have clearly changed and we are now in a position to actively contribute to the promotion of equal opportunities. Physics is open to everyone - and it is a rewarding journey of discovery through this fascinating world.

Ille C. Gebeshuber is Associate Professor of Experimental Physics at the Vienna University of Technology and an expert in bionics, nanotechnology and tribology. She combines interdisciplinary research with science communication and outreach work. If you would like to find out more about her and her work, here is the link to her website.

April 2025

Carolin Hahn, independent Management Consultant, Linz

About myself and my research

I set up my own business as a management consultant almost seven years ago and support companies, but occasionally also research institutions and universities in technology marketing, science communication and strategic issues.

I often act as an interpreter between technicians on the one hand and ‘normal’ people on the other. I benefit from my mix of experience from my physics degree and doctoral thesis in quantum optics, my time in science management at a large accelerator laboratory and an MBA in strategic management, which I added on while working. So I've found a sweet spot and can earn my money doing things that I've always enjoyed and that mostly don't feel like work at all. What I really enjoy is the enormous variety in my everyday life. The topics range from X-ray images of Egyptian mummies to quantum cryptography in space to ‘Hey, we have a very physical set of slides about a fusion power plant, can you prepare it so that we can take it to the Federal Minister of Education and Research?’

As a sideline, I am a mum to two wonderful little people with whom I am currently discovering the world all over again. Here, too, my independence and the freedom that comes with it help me a lot.

What can be done to achieve more equal opportunities in physics?

I think visibility and role models are hugely important - from an early age, so that children don't get the idea that STEM subjects are not for women.

I believe that well-developed childcare is at least as important, because it determines whether a woman comes to work or not. For me, this also includes a partnership at eye level, which unfortunately is often not the case in our society... I have a great husband with whom I can share the family work well. For example, he really has taken over half of my parental leave to keep my back free. In Austria, however, only one per cent of fathers take six months or more of parental leave and the figures are actually falling (see https://www.derstandard.at/story/3000000240848/immer-weniger-maenner-gehen-in-karenz-woran-liegt-das, for example). Unfortunately, it is obvious that this does not necessarily increase equal opportunities, regardless of the field of work. There are many reasons for this, but I always have to think of the beautiful and wise saying: ‘Those who want something will find ways. Those who don't will find reasons.’

If you would like to find out more about Carolin Hahn and her work, you can find the link to her website here: www.carolinhahn.com

May 2025

Doris Stoppacher, Astrophysicist at the University of Seville

About myself and my research

I am an astrophysicist, born in Styria in 1986, completed my master's degree in Graz and then my doctorate in Madrid. I then worked as a postdoctoral researcher in California and later went to Chile for two years on a research fellowship. I have been back in Spain since 2024 and work at the University of Seville.

My main research area is the formation and evolution of galaxies. I work with numerical simulations and computer modelling to investigate how faint, diffuse galaxies form. We have named our project ‘Hidden Figures in the Sky’ in homage to the three African-American female mathematicians.

What can be done to achieve more equal opportunities in physics?

I think that small and consistent steps towards equality are necessary. This starts, for example, with gender-sensitive and gender-equitable language. In English, the term "scientist" is gender-neutral and does not imply the gender of the person it refers to. However, in other languages - such as German or the Romance languages (e.g. Spanish, French, Italian) - scientific professions are often gendered. For instance, German distinguishes between Wissenschaftler (male scientist) and Wissenschaftlerin (female scientist), and Spanish between científico and científica. This influence the perceptions of gender roles in science. The same applies to gender-inclusive language that recognises that we live in a non-binary society.

In German, it has been customary in recent decades to predominantly use the generic masculine. If I only ever talk in German about "male scientists" (männliche Wissenschaftler), "male physicists" (männliche Physiker) or "male professors" (männliche Professoren), the male image sticks and thus reduces the visibility of other genders. Even if it may seem awkward at first to always say ‘scientists and scientists’ (Wissenschaftler und Wissenschaftlerin; científico y científica), this has a positive impact in the long term because girls and women can identify better with these professions as a result. Language shapes our thinking, our imagination and the way we relate to ourselves. I realised this myself when I was learning Spanish. I could no longer use the generic masculine to refer to myself because it is not common in this language.

I regularly give talks at schools where the topic of stereotypes in science is an integral part of the programme. I want to show children and young people how deeply rooted the clichés of the crazy, nerdy scientist and the strangely dressed, unattractive female scientist are in us - and that we often even unconsciously perceive them as funny.

I also believe that men in particular should actively campaign for equal rights and equal treatment. They should take a clear stance and see themselves as allies on this journey. Equal treatment also does not mean treating everyone exactly the same, but rather meeting them individually where they are at the moment - be it in terms of their background, their life experiences or their current circumstances. People with caring responsibilities, for example, have different requirements for their workplace than those without - keywords: academic events in the evening, childcare at conferences, etc. Managers in particular can help to create a fairer working environment by being more responsive to these needs.

One of my negative experiences was that I realised that my opinion often counted less. Male colleagues tended to be promoted, while I was often overlooked or automatically assigned paperwork. Workshops and conferences dealing with the topic of equal rights were sometimes ridiculed or even boycotted.

In retrospect, I very much regret one particular life decision. I have always had a strong interest in science and would have liked to attend a higher technical school, where there were perhaps only two or three girls per year at the time. I often looked at the records of my friend who attended such a school and admired her greatly for it. Unfortunately, as a teenager I didn't trust myself to follow this path. I was also afraid of being exposed to discrimination and abuse. In the end, I did manage to realise my dream and become a scientist - albeit with considerable detours.

My positive experiences include, above all, the equality initiatives that I have learnt about abroad. I think Austria still has a lot of catching up to do in this area. Spanish and South American universities and research centres are far ahead of us in their willingness to talk about this topic. In Austria, I often encounter negative reactions when I talk about gender equality or gender roles, whereas Spain even has its own initiative called ‘Women and Astronomy’. It offers (peer) mentoring and networking programmes that have helped me a lot personally.

If you would like to find out more about Doris Stoppacher and her work, you can find the link to her website here: https://dstoppacher.github.io/

June 2025

Christine Maier, Quantum Engineer at Alpine Quantum Technologies (AQT)

About myself and my research

Even as a child, I was fascinated by the natural sciences, the vastness of the universe, the formation of mountains, animals and plants; but most of all I was fascinated by the idea that there should be something so tiny that I can't see it in everyday life, but at the same time everything is made of it - atoms! At the University of Innsbruck I learnt more about atoms, quarks, electrons and quanta. It soon became clear that quantum physics was going to be my specialism and so I finally completed my doctoral studies in the research group of Prof. Rainer Blatt and Dr Christian Roos at IQOQI Innsbruck. My dissertation focused on setting up, conducting and analysing experiments on a quantum simulator with up to 20 calcium ions in a linear Paul trap, as well as on methods for characterising the states of large quantum systems.

Since 2020, I have been working as a quantum engineer at AQT (Alpine Quantum Technologies) in Innsbruck, building, maintaining and optimising - how could it be otherwise - quantum computers.

What can be done to achieve more equal opportunities in physics?

I think the first step needs to be taken at an early age: namely to encourage children's innate curiosity about nature and technology, regardless of their gender. By this I mean, for example, providing or motivating an introduction to technical toys, reading out nature-related, scientific children's books and small home experiments. This would at least give all children the same opportunity to see engaging with science as a natural, everyday thing and to consolidate their potential interest in it.

The next step is to ensure that young women do not suppress their scientific curiosity due to stigmatisation and ‘fear of stepping out of line’. An important tool for this is certainly the better visualisation of role models such as female physics teachers and active female physicists in industry and research.

Finally, equal opportunities must be ensured in everyday working life, both in academia and in industry. An appeal must be made to employers and politicians, on the one hand with regard to the fair allocation of jobs and on the other hand with regard to better opportunities to combine family planning and a career.

If you would like to find out more about Christine Maier and her work, here is the link to an article about her dissertation (only available in German), here is an article about the dissertation prize she was awarded and here is the link to the AQT website: https://www.aqt.eu/

July 2025

Adriana Settino, Physicist at the Institute of Space Research Institute of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW)

About myself and my research

I am a space physicist focused on understanding how plasma—the ionized gas that fills much of the universe — behaves and impacts our planet. I conducted my studies at the University of Calabria where I achieved my master degree in Physics and my PhD in Plasma Physics. My research has taken me across several countries: from Sweden, to Spain, to Austria, where I currently work as a postdoc at the Institut für Weltraumforschung in Graz. These international experiences have allowed me to collaborate with diverse research teams and contribute to a range of space physics projects in leading institutions.

One of the central topics in my research is the study of plasma instabilities and their influence on the large-scale dynamics of the near-Earth space. An example is the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability, a process that creates vortex-like structures when two plasma flows slide past each other at different speeds. These structures are critical to how energy and particles are transported across key regions in space. By using in situ measurements from several NASA and ESA spacecraft missions orbiting around the Earth, I analyse these structures and compare them with numerical simulations models.

What can be done to achieve more equal opportunities in physics?

If we truly want to achieve equal opportunities, we need to start early—long before university or job applications. Our society is still deeply shaped by stereotypes and rigid ideas about gender roles, often reinforced through something as simple as which toys children are “supposed” to play with or which careers they’re encouraged to imagine. Breaking these patterns requires a strong partnership between schools and families, working together to challenge the outdated notion that certain paths are only for boys or girls. Science should be introduced early, not just as a subject, but as a way to spark curiosity and build confidence. At the same time, it’s essential for students—especially girls—to see real-life examples of women thriving in scientific careers. Role models matter: they show that these paths are not only possible, but also rewarding.

Pursuing a research career often means frequent travels and relocating across countries—or even continents. While this mobility can be exciting, it also makes balancing work and family life incredibly challenging. And in a society where caregiving responsibilities still fall largely on women, it's often women researchers who face the greatest obstacles. As a result, many are discouraged from even entering this path, or eventually feel forced to choose between building a family and advancing their careers. Achieving lasting change means pushing for deeper reforms—starting with awareness among educators, institutions, and policymakers, and expanding to the broader society. We need systemic reforms that rethink how mobility, career progression, and caregiving are balanced. From institutional policies that promote flexible working conditions to cultural shifts in how we value care work, lasting change begins with acknowledging these structural barriers—and working collectively to dismantle them.

If you would like to find out more about Adriana Settino and her work, here is the link to her personal website at the ÖAW, here the link to her Research Gate profile, and the following link to the IWF-website: https://www.oeaw.ac.at/en/iwf/

August 2025

Anna Spindlberger, Technology Development Engineer for GaN Power Transistors at Infineon

About myself and my research

My path to studying physics and my current job was anything but straightforward. Already in secondary school I discovered my passion for puzzles and problem solving, especially in maths problems. I also had the opportunity to take part in the “Powergirls” programme (link), which was initiated by the province of Upper Austria to get girls interested in technical professions. Despite these experiences, however, I decided in favour of a Musical Upper Secondary School, because as a 14-year-old I couldn't imagine being one of the few girls at an HTL (German for Higher Technical Education Institute). At that time, I was still unsure which technical field I was really interested in.

Physics offers a comprehensive overview of many technical fields, which fascinated me in particular when I studied the subject more intensively at secondary school. This encouraged me to choose to study technical physics in order to deepen my knowledge and skills in this field.

I discovered semiconductor physics and the material gallium nitride (GaN) through my master's and doctoral thesis. It was fascinating for me to produce the semiconductor myself and to characterise it using various methods - in other words, to put it through its paces :-)

As a development engineer for power transistors based on GaN, my area of responsibility is diverse. The production of power transistors consists of more than 100 individual processes. For each of these individual processes, there are specialists with whom I work closely to optimise various process blocks (such as epitaxy or metallisation). My task is to develop a product that is as efficient and reliable as possible, while striking a balance with the manufacturing costs.

What can be done to achieve more equal opportunities in physics?

Equal opportunities in physics begin in the early years of childhood. It is important to awaken children's curiosity for science and show them that there is a way to understand and describe the world around us. A first step is to take children's questions seriously and let them experiment to find a solution. This encourages children to discover and expand their abilities.

Another step towards equal opportunities is group work. By having pupils of different genders, social backgrounds and interests working together, we can ensure that all voices are heard and all perspectives are considered. This not only helps to improve communication skills, but also to promote diversity of ideas and solutions.

But what do you actually do after studying physics - as a woman?

Many people think that physicists only work at universities. But the truth is that there are a variety of jobs that are based on physics. Semiconductor physics, for example, is the basis for all modern technology. From the development of smartphones to medical devices - physics is everywhere.

The variety of fields of activity and applications is best illustrated by concrete role models. We need inspiring women and girls with a STEM background who are enthusiastic about their careers. Through these measures, we can promote equal opportunities in physics and help all pupils and students to realise their full potential.

Anna Spindlberger will give a career talk at the 4th Women in Physics Career Symposium of the joint OEPG-SPG Annual Meeting at the University of Vienna on 18 August 2025. You can find more information here.

If you would like to learn more about Anna Spindlberger and her work, you can find a link to her LinkedIn profile here and her contribution to the Science Slam Austria Final 2020 entitled ‘Gallium Nitride: the smart aleck among semiconductors’ here.

September 2025

Bettina Anderl, Astrophysicist and Head of ESERO Austria

About myself and my research

My name is Bettina Anderl. I studied astrophysics at the University of Vienna and also completed a teaching degree in mathematics and physics. After several years in research, I discontinued my dissertation to devote myself to my family and teaching.

Since 2020, I have been the director of ESERO Austria (European Space Education Resource Office). In this role, I connect space topics with school education and support teachers with practical materials, training courses and projects that inspire enthusiasm for science.

I am convinced that space inspires. It is a fascinating way to convey complex scientific content in an understandable, exciting and future-oriented way. Austria is strongly represented in this field, both in research and industry – a potential that we want to make accessible to young people.

What can be done to achieve more equal opportunities in physics?

Equal opportunities are very important to me. It starts with visibility, language and attitude – especially in schools. We need role models that are free of stereotypes, diverse role models and early, low-threshold access to scientific experiences – regardless of gender, origin or social background.

In concrete terms, this means:

• Providing targeted support to disadvantaged groups

• Making career paths visible

• Putting people from the STEM sector in the spotlight

One project close to my heart in this context is our ‘Space Careers’ series: in cooperation with Whatchado.com, we profile people from Austria who work in a wide variety of areas of space travel – including space medicine, space law, space architecture and many other exciting fields that are often not in the spotlight.

I myself have occasionally experienced discrimination during my studies – fortunately not often and not at my home institute of astronomy. Nevertheless, there were instances where women were systematically given lower grades than men. To prevent this from happening today, we need strong awareness – and teachers who are sensitive to equality issues.

If you would like to learn more about Bettina Anderl and her work, you can find a video about her work at ESERO Austria here (only available in german) and a link to her LinkedIn profile here.

October 2025

Barbara Stadlober, Physicist & Research Group Leader at Joanneum Research

About myself and my research

I studied experimental physics at the University of Graz in the 1980s and 1990s – my thesis was on the then highly topical subject of high-temperature superconductors, which I investigated using phononic Raman scattering. I remained faithful to this topic during my doctoral thesis, but not to the KFU – I went to the Walther Meissner Institute in Garching to do electronic Raman scattering on the HTCs – it was an exciting time.

After completing my doctorate, I worked at Infineon Technologies for six years (and had two children during that time) – but research never left me, so I seized a great opportunity in 2002 to set up a research group at Joanneum Research, which is now called Hybrid Electronics and Patterning and comprises 25–28 scientists. We deal with printed electronics and large-area micro- and nanostructuring, as well as all aspects of these topics, from the development of new materials, processes and devices to electronics and applications. Practical application plays a major role for us, and we are delighted when our research results are physically reflected in reality, whether as part of a product or a process flow.

What can be done to achieve more equal opportunities in physics?

We have a very good atmosphere in the group, and a great mix both in terms of disciplines (physicists, chemists, biologists, electrical engineers, geologists, process engineers, etc.) and in terms of age and background. It is important to me that everyone does what they want to do and what they are good at. I don't believe in treating everyone the same – everyone needs their own niche where they feel comfortable, then they can be productive. This works very well in a sufficiently large group like mine – I also have many permanent employees who have been at the institute for several years. But of course there are also students. For women (and for men at our institute), it is important to have complete flexibility in working hours. Many children have been born in my group, and contrary to popular belief, parental leave has no negative effect on scientific productivity. Sometimes it's good to clear your head at home – children ask clever questions. I have several scientists who work part-time (50-80%) and do research, and they enjoy it and produce very good results.

I have not personally experienced any inequality. However, I have carefully selected my superiors and mentors and have also turned down career opportunities when I was not convinced by the human qualities of those involved.

If you would like to find out more about Barbara Stadlober and her work, here is the link to her website profile at Joanneum Research, here is her LinkedIn profile, here is her ORCID profile and here is the link to the working group she heads.

November 2025

Ursula Palfinger – Physicist at the MATERIALS Institute (Institute for Sensors, Photonics and Manufacturing Technologies) at JOANNEUM RESEARCH

About myself and my research

Even as a child, I was fascinated by how things work. Fortunately, my parents rarely stopped me from unscrewing a VCR or cutting open a floppy disk. I had an inspiring physics teacher at school, and in my environment, it was never questioned that a woman could pursue a technical career.

After graduating from high school, I studied physics (and a bit of astronomy on the side) at the University of Graz. My passion has always been in experimental work: preparing samples, making effects visible, taking measurements, and exploring outcomes. During my diploma thesis, I first encountered micro- and nanostructuring. In my subsequent doctoral studies – supervised by Associate Professor Dr. Joachim Krenn (University of Graz) and Dr. Barbara Stadlober (JOANNEUM RESEARCH) – I focused on new methods for fabricating ultra-fine structures for printable electronic components and on the growth of organic semiconductors.

I have now been working for nearly 25 years at JOANNEUM RESEARCH MATERIALS in Weiz, in the research group “Hybrid Electronics and Patterning,” as a physicist and project manager. We use micro- and nanoimprint processes to create structured surfaces. Depending on the size, type of structure, and material, these surfaces exhibit altered properties. For example, water may run off very easily or not at all; the surface may have more or less flow resistance due to its structure, or it may scatter, reflect, or focus light. The applications are diverse and can be found in lighting elements and displays (for glare reduction or shaping light distribution), in biomedical sensors (for optical readout or microfluidic transport), or even in aviation (to increase efficiency and save fuel).

Technically, my main area of responsibility is the replication of structures that, due to their complexity, can often only be initially produced on small areas. Using so-called step-and-repeat imprinting processes, these structures are scaled up to industrially relevant dimensions. I lead national and international research and industry projects in this field.

I am also the proud mother of two wonderful teenagers whose interests could hardly be more different. As parents, it is important to us to encourage them to believe that every subject and every future career path is open to them.

What can be done to achieve more equal opportunities in physics?

Equal opportunities in scientific careers begin long before the first research project – namely, when children and young people start discovering the world, developing an interest in nature and technology, and encountering physics and chemistry at school. These subjects are often burdened with the prejudice of being complicated and dry. I believe this reputation may discourage girls more than boys, leading to early resignation. What’s needed are engaged parents, inspiring teachers, and well-equipped school facilities where students can work independently under guidance. Lots of hands-on experience and discovery, rather than just watching; learning necessary formulas not just by heart, but by truly understanding them.

Technical interest is also fostered by role models and opportunities for exchange (holiday programs, workshops, networks). In university and professional life, transparent selection processes, targeted support for young talents, and good work-life balance – even at higher career levels – are essential. This applies equally to women and men.

Research thrives on communication and teamwork. When diversity of talent is seen as a driving force and people are assigned roles based on their strengths, real momentum is created. The best ideas don’t emerge where everyone thinks the same, but where different perspectives meet constructively. Equal opportunity is therefore not a “nice-to-have,” but a real asset for physics and research and development in general.

In our research group – led entirely by women, which is still quite rare – this principle is truly lived, and the success speaks for itself. However, I have also sat in scientific symposia with 150 men and maybe five other women, where the low proportion of women in senior scientific positions becomes very apparent.

Women and men are equally suited for scientific and technical education and careers – in fact, they complement each other excellently in research teams. Especially in research, flexible working hours or flextime models can generally allow for a good work-life balance. However, leadership positions with technical and economic responsibilities still often come with all-inclusive contracts, high time commitments, and travel requirements, which can conflict with family life. Here, it would be desirable for scientific institutions and companies to be open to new models, such as shared leadership roles.

The higher the proportion of women in technical education and careers, the more we can drive further developments together. I definitely want to encourage young women with an interest in science to pursue this path and help shape the future.

“I am among those who think that science has great beauty. A scientist in his laboratory is not only a technician: he is also a child placed before natural phenomena which impress him like a fairy tale.” – Marie Curie (Nobel Prize winner in Physics, 1903, and Chemistry, 1911)

If you would like to find out more about Ursula Palfinger and her work, you find the link to her website profile at Joanneum Research here, her LinkedIn profile here, an article about her work on the BMIMI website here, and a link to the working group she is part of here.

December 2025

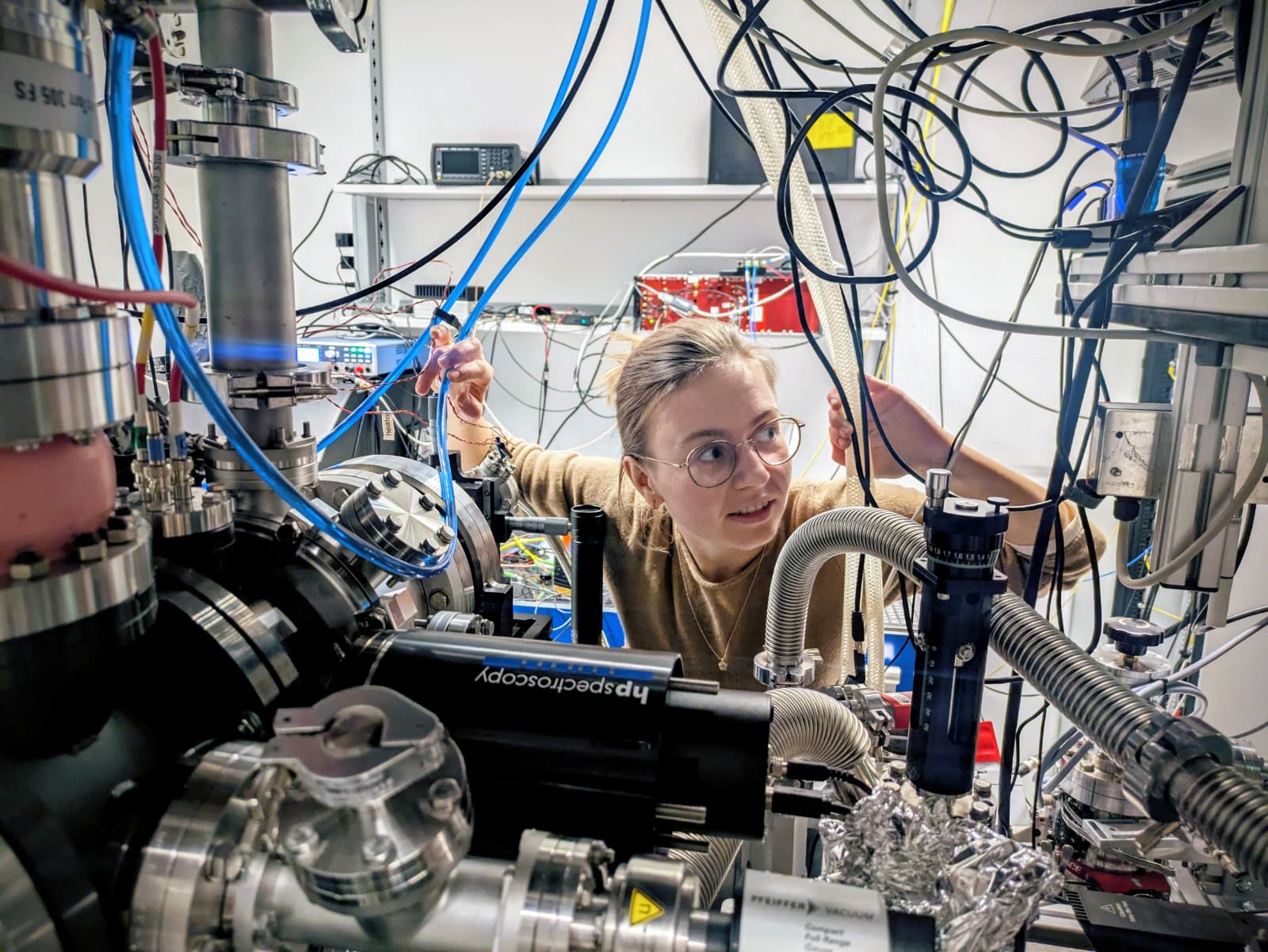

Ira Morawetz, PhD student at the Atomic Institute of TU Vienna and winner of the Berta Karlik Poster Prize 2025

About myself and my research

My love for research and especially physics started back in high school where I was lucky enough to be taught by a very motivated and passionate physics teacher who organized an amateur astronomy group for his pupils. In this group I was able to have a peak into experimental physics research by performing luminosity measurements of variable stars. This experience made me fall in love with the subject, so studying physics was the obvious choice for me. I finished my master’s degree at TU Wien in 2024 and am currently pursuing my PhD in experimental quantum metrology at the Atominstitut of TU Wien in the group of Prof. Thorsten Schumm. Our goal is to develop a nuclear optical clock which can serve as a new ultra-sensitive tool to measure physics beyond the Standard Model. In contrast to optical atomic clocks, our clock transition is not an electronic transition but a nuclear transition. Specifically, we use 229Th due to its uniquely low-lying first isomeric state.

What I enjoy most about my job is solving new problems every day and working together with my amazing team of colleagues.

What can be done to achieve more equal opportunities in physics?

To provide equal opportunities for women in physics and other STEM fields, it is vital to have positive female role models. This can help make the natural sciences a less intimidating environment for girls to get into. Furthermore, it is important to show aspiring physicists that not only exceptionally talented women might have a chance at success in this field. It is my experience as a relatively young researcher that these factors have an impact on the career choices that women make. For women already in the field it is important to have networks of other women to mutually support each other. This is especially helpful if one does not have immediate female colleagues.

Overall, I believe we should move towards making the sciences a less unfriendly environment for all people who want to start a family. Not only women would benefit from less volatile contracts and unsecure employment conditions.

Ira Morawetz has won this year's ÖPG Berta Karlik Poster Prize for young female physicists. If you would like to learn more about her and her work, you can find the link to her research group here and the link to her ORCID profile here.